Contentment

Let’s consider the growth in productive capacity per person from $92.50 a year in 1 CE (AD) to 2020’s $8,968.36

What is your image of yourself? Who do you ‘imagine’ yourself to be?

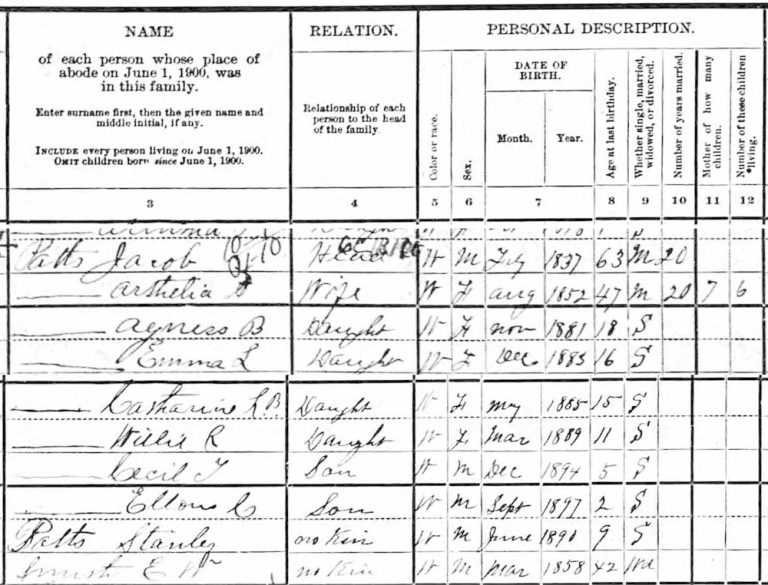

The accompanying family portrait includes my maternal grandfather Stanley Potts (third from right) just before his tenth birthday. The family is three generations of the Jacob Potts family of Piney Creek, Pennsylvania. In this 1900 photo you might expect that Stanley was the offspring of Jacob Potts but the other image is of the U.S. 1900 Federal Census showing Stanley on the next-to-the-last line. Above him are listed Jacob, his wife and their children; below Stanley is the ‘boarder’ counted as part of the census household. But Stanley is none-of-these classifications—the designation after his name is “no kin” and classified him as not family. He never knew who his parents were for there were no records of his birth. He spent a lifetime trying to make sense out of being ‘no kin’.

Stanley spent a lifetime defining himself: he was a woods worker in West Virginia at 17, worked in the Pittsburgh steel mills at 18, moved west to the Dakotas at 20, homesteaded near Lismas, Montana at 25, served in the WW I Army beginning 1917 and rose to the rank of First Sergeant in the Occupation Military Police Corps before his discharge in 1920. Back to the homestead to finish “proving” the homestead July, 1920. Homesteading along the upper Missouri River meant clearing unimproved land of the scrub brush and trees with an axe, building a shanty, getting crops in the ground and surviving. He eventually married, had six children (two of which died at birth or in infancy), built a log cabin and slowly improved his holdings. When Fort Peck Dam flooded out the farmland, he moved his family to western Montana and began farming there. Over the years he slowly increased his holdings and the size of his family eventually included dozens of grandchildren and even more great-grandchildren. He sold his farm to his youngest son and ‘retired’ to live out his later years, dying in 1986 at 96 years old.

But, that identity thing always nagged him. He took many trips back to Pennsylvania and Maryland to visit members of the family and community friends of his youth but never was convinced of his heritage. While he was successful as a man, he always had a gap in his relationship with himself. In 1976 he finally decided that he would let God be his Father and that filled the lack in his satisfaction of being someone of intrinsic worth. What he never felt he received from man, he did get from God.

Stanley had spent more than twenty-five years sitting in his traditional location at the Little Brown Church and endured hundreds of sermons from several pastors and while accepted as part of the church had never got personal with God. A self-made man, he always figured he needed to measure up, to be better, before God would want anything to do with him.

We never really knew why he decided one Sunday that it was time to meet God—he was pretty private about emotional stuff (that veteran sergeant thing) but Someone met him and he changed. I recently read a devotional article which reminded me of his giving up and letting God be God instead of Stan trying to fix himself. Kristin Demery writes in her devotional “Behold” quoting 2 Corinthians 3:18 that,

“And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit.” 1

Kristin notes that the word “beholding” isn’t the simple word for looking but rather katoptrizō meaning to see as reflected in a mirror.2 There is a significant difference between looking and the intensity of seeing the depth of a reflected image—especially if it is God’s image that we see ourselves through.

Our current cultural fascination with creating our own identities is beginning to show the same weakness that my grandfather faced fifty-ish years ago. Creating our own identity rests upon the foundation of our inability to be God – we can do all in our ability to be someone or something else but we do not have the ability to transform our inner nature. If we do ‘create’ the illusion of acceptability to ourselves we risk the trauma of facing the tests of life beyond our abilities to satisfy to our expectations. When we take a philosophy that requires our sufficiency to be someone beyond ourselves, we likely will face the chaos of disillusionment when we can’t make it complete our expectations of ourselves.

Grandpa found completion in giving up on his own sufficiency.

Let’s consider the growth in productive capacity per person from $92.50 a year in 1 CE (AD) to 2020’s $8,968.36

‘Once upon a time’ a man was drawing large crowds, had become quite popular, was being followed by way more

“The natural person does not accept the things of the [Divine] for they are folly to him…” Man, left

Beginning in 1862 and continuing through the 1920s, over one-and-a-half million citizens were given the opportunity to ‘homestead’ their own

Our current cultural fascination with creating our own identities is beginning to show the same weakness that my grandfather faced

Only as Truth fits these criteria does it become meaningful for all and rather than be defined as empirical becomes

American exceptionalism had become a government philosophy as early as the first half of the 19th Century and that the

The painting (American Destiny) was commissioned to encourage, even glamorize, the push west. There is an implicit moral overtone that